UrbanCare Berlin is a community-led project that proposes to generate 2 to 3 pedestrian Loops 2 km long each, connecting neighborhood priority destinations such as schools, playgrounds, medical offices, elderly homes, and supermarkets. On this webpage, follow the Bötzowviertel case, a neighborhood streetscape analysis with pedestrian solutions.

Part one summarizes the UrbanCare methodology and its tools used for the case study.

Part two has four icons: spatial inequity, urban heat, surface runoff, and biodiversity loss. Each shows neighborhood-level data and national, regional, and city-level policies and resources available.

Part three invites participants to walk Bötzowviertel’s walkways by taking an immersive journey with the BHL Data Viewer.

The basic idea of a superblock is to connect a grid of 9 to 12 city blocks with walking, biking, and expanded green spaces, leaving cars at the perimeter. This urban planning concept pioneered in Barcelona (ES) is a trend in many cities, and Berlin is one of them through the KiezBlocks initiative promoted by Changing Cities e.V.

Berlin’s urban landscape has Kieze (neighborhoods in Berlinerisch) comparable in size to a Superblock demanding comprehensive retrofits. Despite our Kieze being public and lively, street-level surfaces are sealed, trapping dangerous urban heat, rainwater is not used and lost, the greenery is weak for biodiversity, and walkability for vulnerable groups to priority locations is in question. In Berlin, what resembles a Superblock concept is heavy traffic lanes framing our Kieze but, most importantly, cohesive communities determined to lead transformational change.

Superblocks in Barcelona are entering a new phase in planning, their connectivity through green corridors to enhance liveability while making traffic adapt to its configuration.

In Berlin, the most recent draft of the Senate’s Mobility Act supports creating the Pedestrian Planner role for each of its 12 districts. The setting is favorable for retrofitting street environments within neighborhood limits and connecting to closeby ones, as Barcelona aims to do.

UrbanCare is a methodology developed by Building Health Lab that applies systems thinking and a comprehensive strategy for developing climate-fit walkways. It aims to improving the local climate, restore biodiversity levels, optimize energy efficiency levels of nearby buildings, avoid spending on water treatment, and consequently battle the rise of urban-associated diseases. By analyzing the city’s environmental data and conducting onsite neighborhood research, we want to inform and assist citizens in making solid arguments for local governments to build healthy green streets and bridge neighborhoods across the district with a pedestrian-first approach. Click to learn more!

This case presentation has three main parts starting with an overview of the UrbanCare methodology and the tools used for the case study.

The second part highlights the main findings on spatial inequities, urban heat, surface runoff, and biodiversity loss found with neighborhood-level research.

The third part invites participants to walk Bötzowviertel’s walkways by taking an immersive journey with the UrbanCare Data Viewer.

UrbanCare is a practical framework to develop climate-sensitive pedestrian environments.

It assists citizens and planners to visualize climate and health stressors at the neighborhood level and participate in creating possible solutions.

15-minute neighborhoods for everyone!

One health solutions! Good for people and the planet.

Align urban development goals to reach the transformative benefits of climate adaptation.

Berlin wants to move away from spending on sidewalks and invest in climate-adaptive pedestrian environments. For this purpose, the city counts on expertise and research at the district level, such as the TU-Berlin 2020 Berlin Pankow Mobility Report. However, there is room for practical guidance to channel broader participation and gather neighborhood evidence for climate, energy, and health projects.

UrbanCare ensures a smooth flow of knowledge through its methodology and intuitive tools by all stakeholders, especially residents. With a neighborhood scale and focus, the tools are practical for people to confidently identify challenges to their daily errands and life outdoors and contribute to possible solutions.

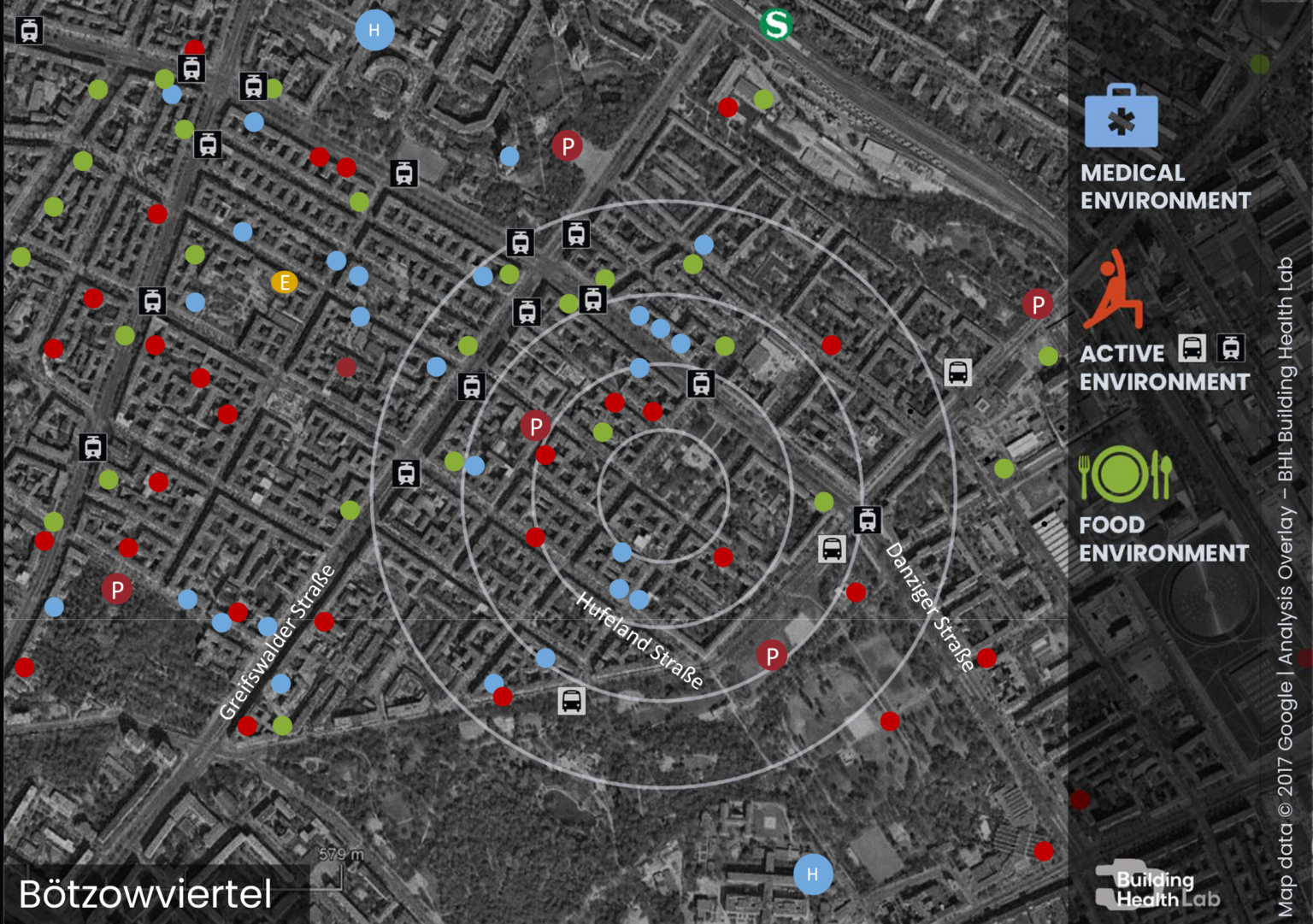

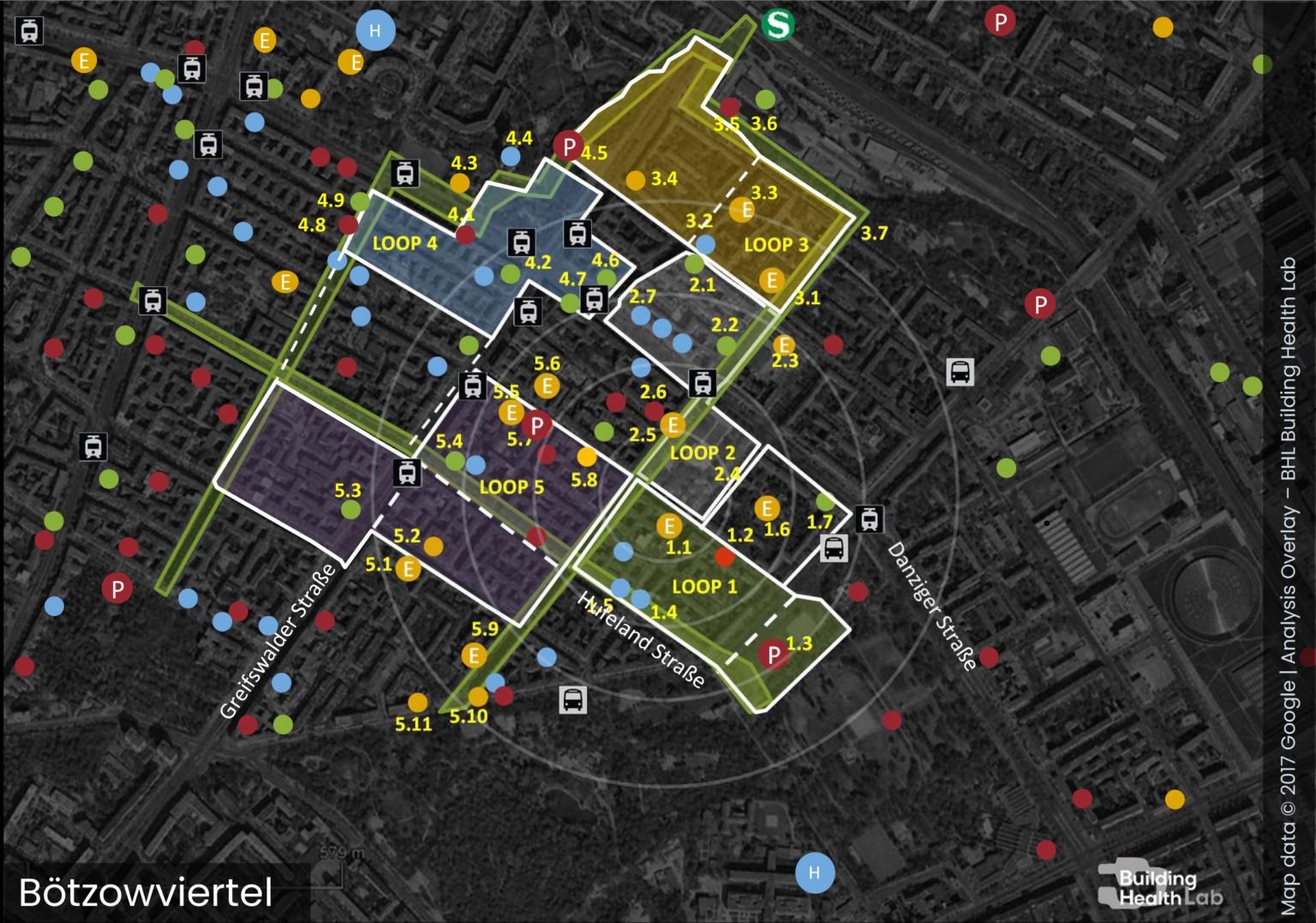

Using google maps, the first step is to identify and map neighborhood priority destinations (points) located at most 1 km away from tram stops and the Greifswalder Str. S-Bahn.

A diverse mix of commercial and cultural attractions are found such as the Kurt-Tucholsky Library, Filmtheater am Friedrichshain, Arnswalderplatz square, the emblematic park Volkspark Friedrichshain(3), as well, numerous, elderly homes, medical offices, schools, and playgrounds.

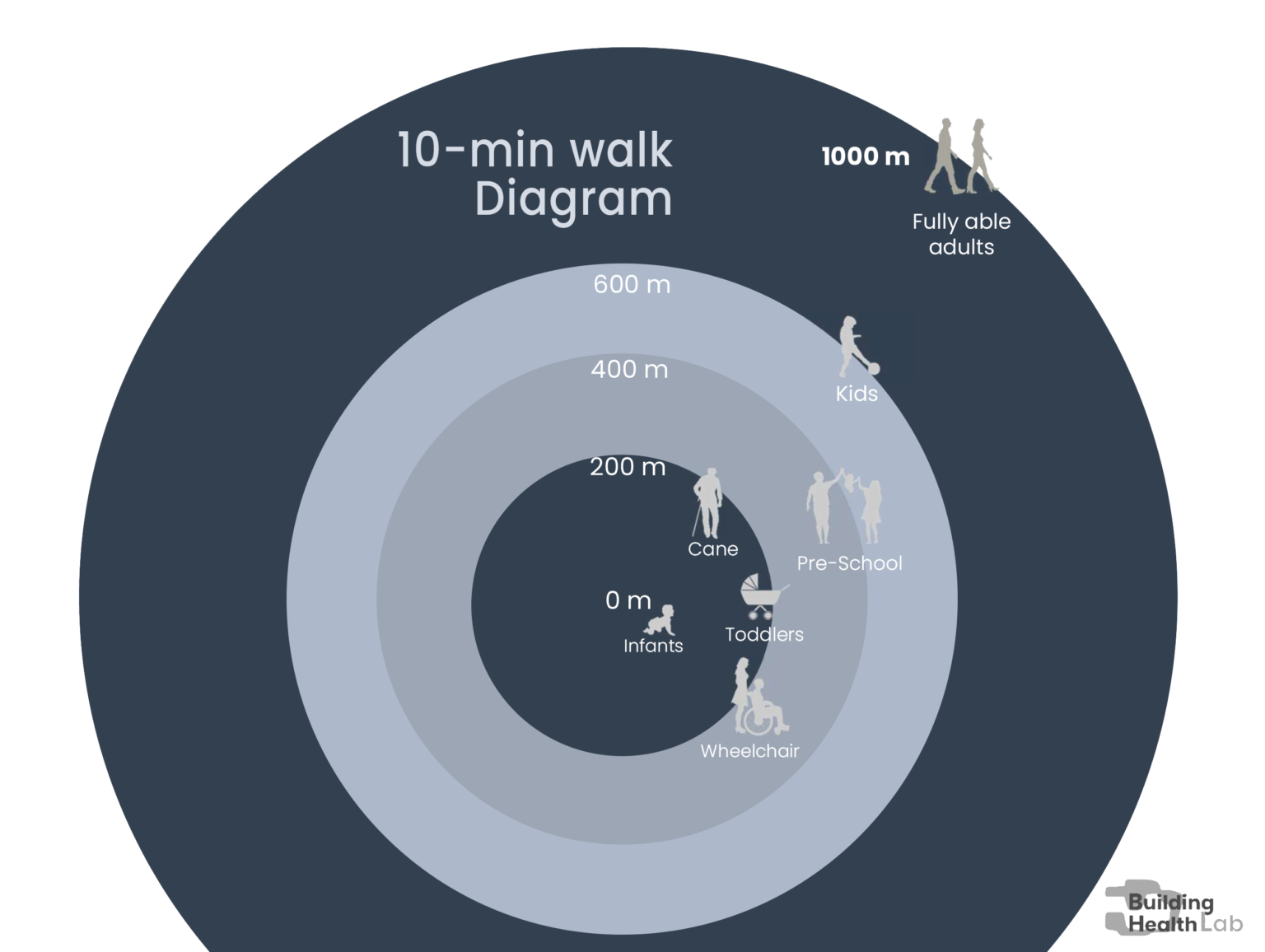

A demographic study helps estimate the gait speed of the slower groups, including children, the elderly, and people with disabilities. Knowing the location of priority destinations and the gait speed of slower groups, we understand how wide avenues such as Danziger Str. and Greifswalder Str. can impact the daily life of most residents. With the information, the field research enters preparation.

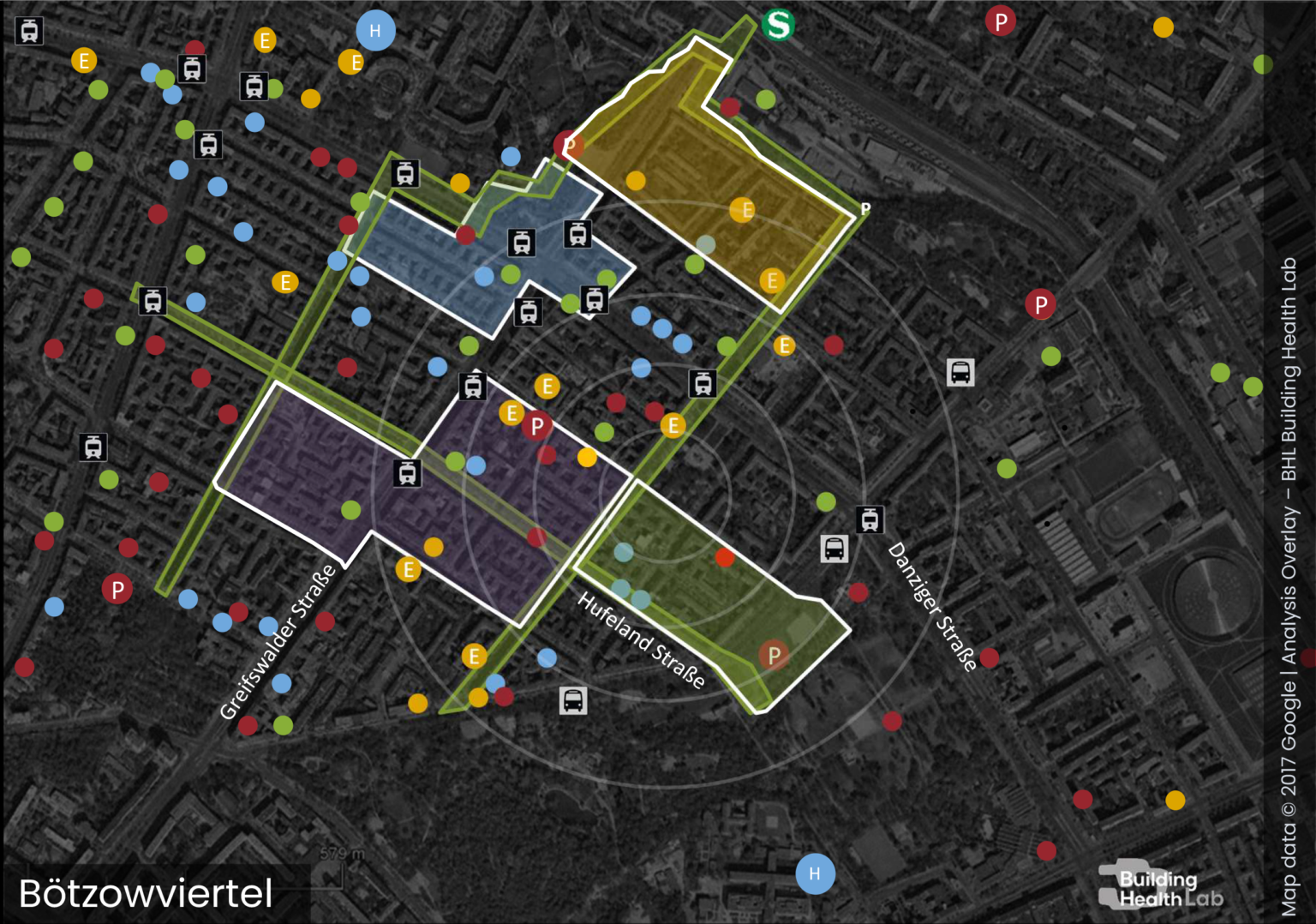

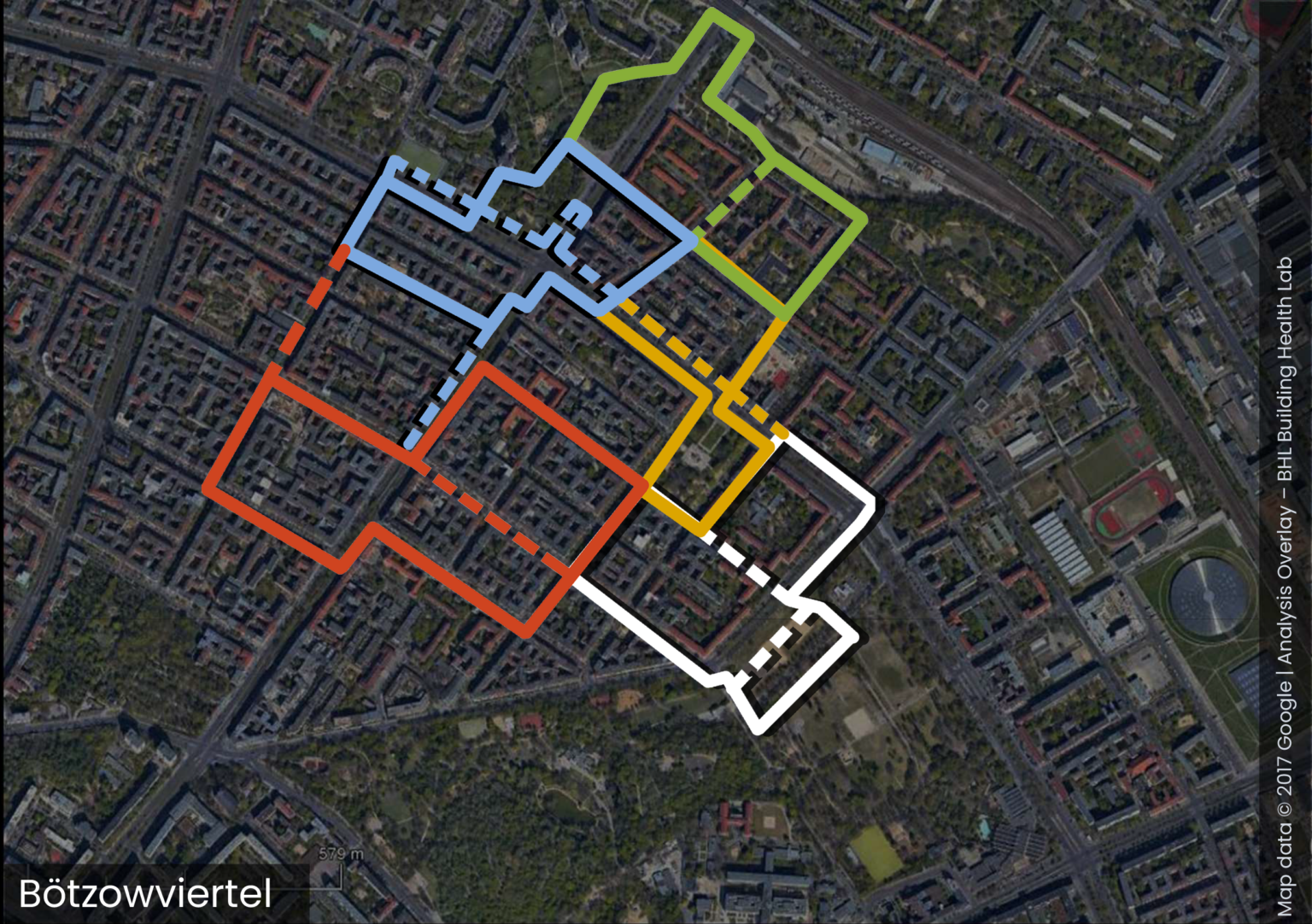

Sidewalks and other walkways (lines) connecting the priority destinations render “Pedestrian Loops” or possible continuous walkways within neighborhoods ideal for people to do daily errands, go to work, school, or play comfortably and safe from street threats.

The loops are templates to fill in the data from four field surveys: spatial inequity, urban heat, surface runoff, and biotope loss.

As urban development intensifies, congestion and environmental degradation also increase. Sealed pavements taking over green soils result in rainwater runoff and hazardous urban heat spots impacting soil, water, and air quality. Among these, streets have historically formed impervious layers disrupting hydrological cycles, requiring expensive stormwater infrastructure to manage stormwater runoff and protect ground and surface water quality (4). The consequence is an environmental degradation capable of destroying local ecosystems, habitats, wildlife, and our health (5).

Our GIS survey defines the neighborhood destinations and walkways (points and lines) forming safe and comfortable pedestrian priority routes we call pedestrian loops.

The field research phase starts along the loops with four systematic environmental surveys and a 360° photography assessment to study conditions and possible impacts on the local ecosystem, especially for pedestrian health.

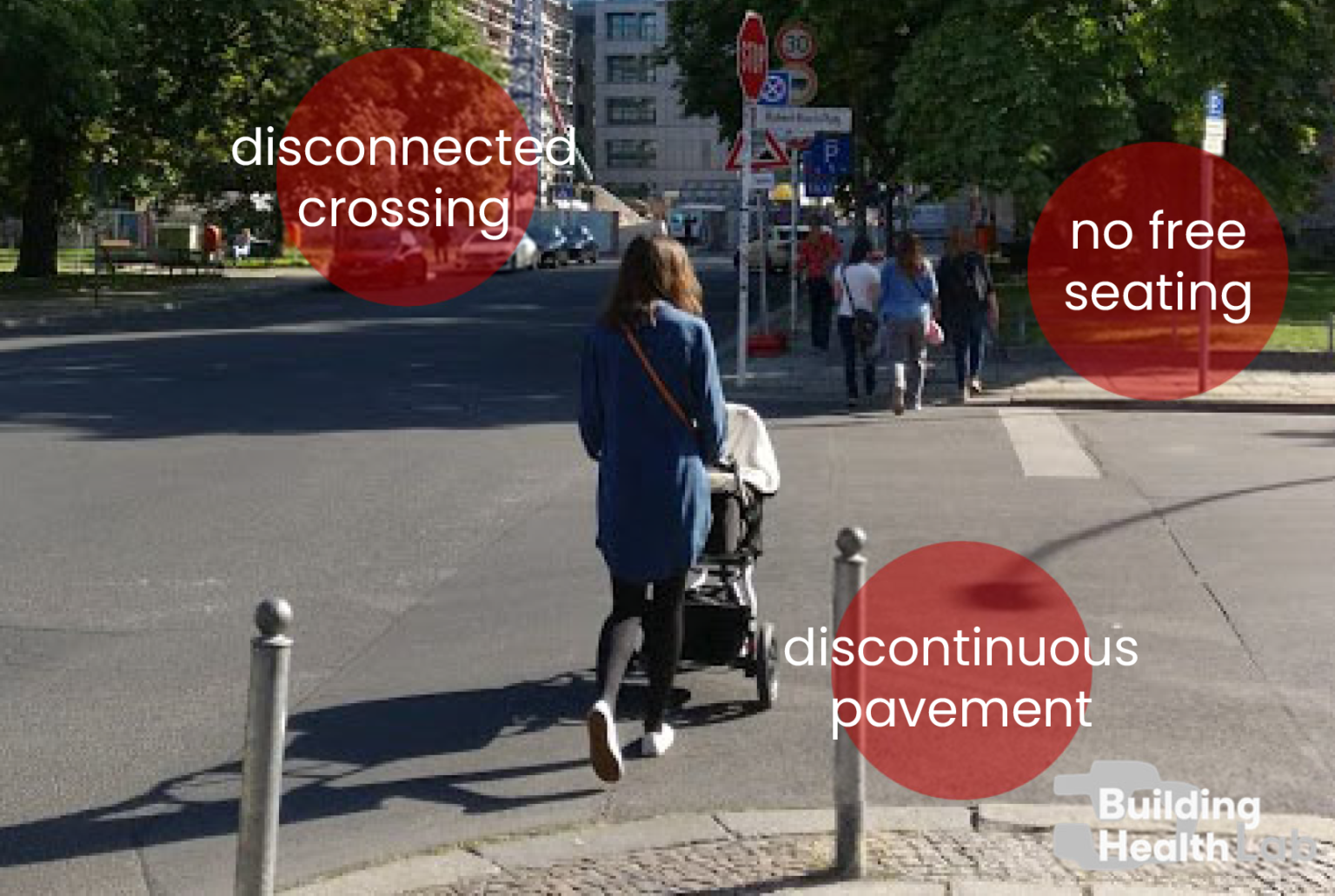

Globally most cities are not designed to meet the gait speed and requirements of slower groups. Berlin is not different. Many streetscape elements and features hinder physical access to services, complicate travel navigation, make public transportation inconvenient, decrease chances for recreation or represent a direct health threat to slower groups.

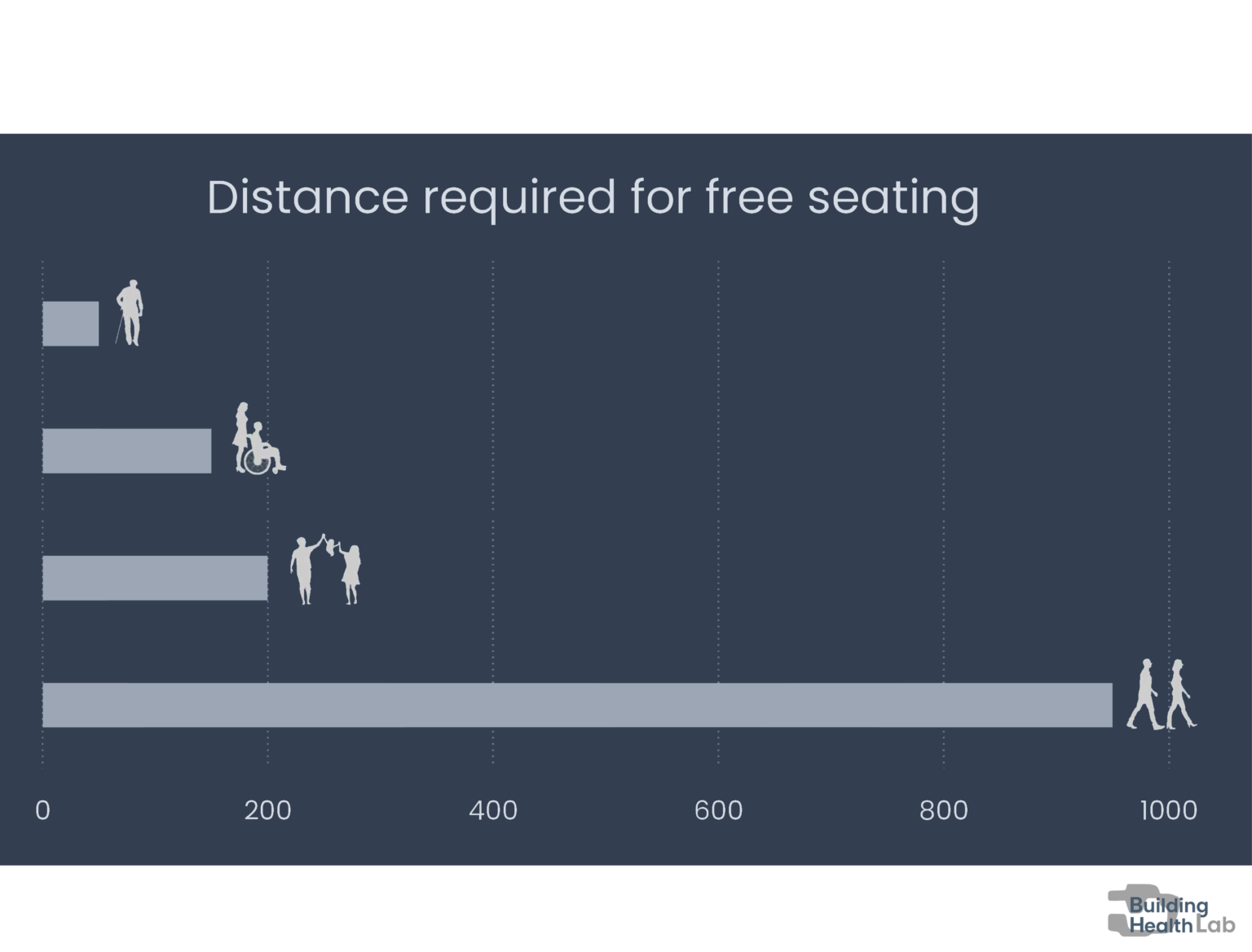

Along with the pedestrian loops, a systematic observation method is applied to record pedestrian obstacles and threats at four types of urban points: (i) stops and stations, (ii) street crossings, (iii) free seating or respite areas, and (iv) spaces at entrances to priority destinations.

In June 2021, the first heat wave of the year temporarily made Germany the hottest region in Europe.

In 2003, 2006, and 2015 – more than 6,000 deaths were attributed to heat. In Berlin alone almost 500 people died of heat-related causes in 2018 (6). This summer 2022, temperatures have soared up to39 degrees Celcius (7).

Surface and air temperatures are not the same. Our measurements show surface temperatures, which by contact also affect pedestrians.

Heat spots are captured with the FLIR E54 and E76 handheld thermal cameras. Both have 320 ×240 pixel detectors that accurately measure temperatures up to 650°C (1202°F) to produce digital and thermal imagery.

A 24° lens is used for short-angle inspections of urban furniture, building entrances, and other walkway situations.

A 42° lens allows wide-angle inspections to measure street sections up to 12 meters.

According to the German government’s current climate impact and risk report (8) , the risk of heavy rain and flooding will be highest in cities such as Berlin as extreme weather is expected.

With data from Berlin’s environmental atlas and simplified surface runoff tools, calculations are made and shown in the viewer in two formats easy to grasp.

1. The urban scene from the user’s standpoint shows hard and soft surfaces allowing different seepage levels affecting climate comfort and pedestrian quality experience and health.

2. Using a satellite photo (upper left), we locate the user’s standpoint to estimate surface areas (m2) for the different surface types and calculate a percentage of sealed surfaces.

In Berlin, urban heat and stormwater runoff have led to the development of green tools such as the biotope area factor (BAF) targeting:

• excessive soil sealing,

• insufficient groundwater storage from avoidable and costly sewage use,

• lack of humidity and extreme heat,

• ever-decreasing habitat due to insufficient green spaces.

Following the BAF calculation principles, biotope loss estimations are done and represented in two ways.

1. The urban scene view shows patches of green and grey surfaces which helps understand the degree of vegetable fragmentation.

2. The satellite map view has a catchment area from the user’s standpoint used to measure permeable surfaces and estimate the green to grey ratio.

Along the loops, we take 360° photos and prepare the data collected into intuitive infographics that explain environmental impacts on health and opportunities for improving the local climate.

The infographics are embedded into a web-based immersive journey similar to google streets but from a pedestrian perspective. This immersive data viewer allows communities and stakeholders to navigate the neighborhood, rate its urban scenes, and sign petitions for change!

Click here to see this process in one of our neighborhoods.

The Data Viewer brings new insights about the neighborhood especially to pedestrian planners on developing efficient actions with accurate outcomes.

Some actions for Bötzowviertel that may upscale for Berlin include:

• Enhance crossings at street intersections with intuitive pedestrian-centered designs;

• create new fully pedestrianized crossings at mid-blocks;

• retrofit underused sealed pavements and surfaces along streets, sidewalks, and middle islands;

• integrate biking projects – such as the ‘Hufelandstraße Bike Street project’(9) – to the pedestrian plan;

• provide sheltered free-seating where strategically needed by vulnerable groups, and,

• condition stops for buses and trams with climate-friendly solutions.

The following section gives an overview of the regulatory policy and resources available at the national, regional, and city levels that may support improving urban ecosystems for pedestrian health at the neighborhood scale.

Click play to watch challenges for pedestrian planning

Evaluations are performed to assess street level needs and requirements of children, the elderly, and people with different kinds of physical and/or cognitive impairments or disabilities.

Pedestrian Planning

is a new amendment to the city’s mobility law that came into force on February 24, 2021. It gives greater rights and protections to pedestrians – people on foot, in wheelchairs or otherwise – in the German capital.

Measures outlined in the law include aids to crossing streets, such as longer green crossing times and more direct routes, traffic calming measures, better lighting, and more sitting space and ‘play streets’.

The original Mobility Act, ratified in 2018, was the first in Germany to give priority to public transport and bicycle traffic over private cars.

This new amendment is the continuation of the city’s work to shift the focus on Berlin’s roads away from private car traffic (10).

Prokiez Bötzowviertel (owners)

Through this association, Kiez residents (and friends) are invited to participate in events and find out interesting things about the neighborhood, change or preserve something.

Kiez & Kurt is the neighborhood’s meeting center “launched” in 2018 with the aim of making the neighborhood more colorful and lively! (11)

Fuß e.V. (advocates)

Since 1985 FUSS e.V. has been representing the interests of pedestrians in Germany. We are a contact partner for administration, politics and the general public regarding all questions about walking. We issue statements and propose amendments to laws and directives.

With our expertise and experience, we advise citizens, administrations and politicians and support local and regional initiatives with regard to specific traffic problems. We carry out pilot projects for pedestrian-friendly traffic solutions together with other organizations and administration departments (12).

• Health costs are reduced by introducing a more active lifestyle.

• Transportation costs drop due to less fuel consumption and infrastructure (development and maintenance) of other travel modes.

• Walking tourism promotes and preserves heritage from erosion and pollutants.

• Local business activity and employment increases substantially; pedestrians have 40% more time at shop windows.

• A 10 point increase in walkability levels (not walking rates), may increase property values by 5 to 8 percent.

Thermal surveys at pedestrian level at different locations were realized to help identify heat spots hazardous to people and in detriment to energy efficiency. Click for a thermal report sample in PDF.

“Germany acknowledges that increasing heat is an emerging health hazard and some states have taken good first steps to help at-risk populations adapt,” said Katharina Rall, senior environment researcher at Human Rights Watch. “But given the urgency of both reducing emissions and addressing the effect of the climate crisis, German authorities need to step up their game.”

There is limited data on heat-related mortality in Germany. But during each of the previous heat waves – in 2003, 2006, and 2015 – more than 6,000 deaths were attributed to heat. Limited data from 2018 shows that almost 500 people died of heat-related causes in Berlin alone (13).

can save cooling energy costs up to 19% with heat mitigating solutions; and up to 20% in heating costs with wind breaking vegetation (14).

Surface analyses determine the porosity and heat retention capacity of various hardscape materials at the site.

Stormwater Management & Planning

A substantially revised version entered into force in March 2010. This amendment completed the transposition of the EU Water Framework Directive (WFD) into German national law and allowed the German Länder to adapt their respective water acts to the European provisions (15).

The BlueGreenStreets research project investigates and evaluates the effectiveness of existing planning instruments and regulations on

The aim of the project is to further develop these instruments with a focus on the sustainable and resource-efficient design of urban neighborhoods (16).

• Typical fee (Berlin): ~2 €/m²/year

• Examples for fees

a) Private house (150 m² connected) 300 €/year

b) Supermarket (10.000 ² connected) 20.000 €/year

c) Supermarket (disconnected, infiltration) 0 €/year (17).

The amount of hard surface in comparison to green ones are measured and the ‘Biotope Ratio’ is estimated.

Biodiversity Planning

The Berlin Strategy for Biodiversity Preservation was created in March 2012 by the Berlin Senate. This strategy provides the foundations for fulfilling Berlin’s part in the global responsibility to preserving biodiversity (18).

Biodiversity Policy Lab

The Biodiversity Policy Lab (BPL) is a research unit of the Museum für Naturkunde Berlin that analyses biodiversity policy, advises on biodiversity policy and accompanies or even actively initiates public debates on biodiversity policy. The aim of the BPL is to make the diversity of species, genes and ecosystems a public matter – a matter that societies must take care to preserve and use according to sustainability criteria (19).

A biodiverse field installation costs the same as lawn: around 8 € /m2. Considering the maintenance costs of cutting a lawn 10 times a year at 2.50 € /m2 to that of a field needing cutting only twice a year at 0.60 € /m2, the installation costs of a field of native flowers will have paid for itself in around four years while saving the company a annual of 1.90 € /m2 (figures obtained from landscaping firms).

For butterflies, bees, and bumblebees, the investment reaps benefits in the first year.

Bötzowviertel Field research in Kms

Pedestrian loops: 8 km

Street grid: 14 km

Bötzowviertel Data Analysis Reports

Other UrbanCare cases developing across Europe

Collaborating partners

Alvaro Valera Sosa (2021)

Update July 2022

BHL Building Health Lab

Alvaro Valera Sosa: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Analyses

[email protected]

BHL Building Health Lab

Alvaro Valera Sosa: Original draft, Writing-reviewing, Editing, Design, Administration.

Netra Naik: Draft assistance, Software, Data curation.

Julia Reißinger: Software, Data curation.

1. Gartz, K. (2013, August 28). Kiezbummel in Berlin-Prenzlauer Berg : Das Bötzowviertel hat Grund zum Feiern. Der Tagesspiegel. https://www.tagesspiegel.de/berlin/kiezbummel-in-berlin-prenzlauer-berg-das-boetzowviertel-hat-grund-zum-feiern/8700982.html

2. Berlin Senate. (2011, May). Ausstellung Sanierungsgebiet Bötzowviertel eröffnet. Https://Www.Stadtentwicklung.Berlin.De. https://www.stadtentwicklung.berlin.de/nachhaltige-erneuerung/prenzlauer-berg

3. Pro Kiez Bötzowviertel e.V. Berlin – Entdecke den Bötzowkiez im Prenzlauer Berg. (2020). Prokiez. https://www.prokiez.de/

4. Streets are Ecosystems. (2017, June 29). National Association of City Transportation Officials. https://nacto.org/publication/urban-street-stormwater-guide/streets-are-ecosystems/

5. WHO (2015). CLIMATE AND HEALTH COUNTRY PROFILE – 2015 Germany. https://apps.who.int/iris/rest/bitstreams/1031213/retrieve

6. An Der Heiden, M., Muthers, S., Niemann, H., Buchholz, U., Grabenhenrich, L., & Matzarakis, A. (2019). Schätzung hitzebedingter Todesfälle in Deutschland zwischen 2001 und 2015. Bundesgesundheitsblatt – Gesundheitsforschung – Gesundheitsschutz, 62(5), 571–579. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00103-019-02932-y

7. Berlin Senate. (2022, July 19). Up to 39 degrees: Heat wave reaches Berlin. Berlin.De. https://www.berlin.de/en/news/7634442-5559700-up-to-39-degrees-heat-wave-reaches-berli.en.html

8. Matera, E. (2021, July 21). How will climate change impact Berlin? Berliner Zeitung. https://www.berliner-zeitung.de/en/how-will-climate-change-impact-berlin-li.172154#:%7E:text=Berlin%20and%20the%20surrounding%20state,greatest%20in%20cities%2C%20including%20Berlin.

9. Schubert, T. (2021, June 14). Prenzlauer Berg: Hufelandstraße wird zur Fahrradstraße. Berliner Morgenpost, Berlin, Germany. https://www.morgenpost.de/bezirke/pankow/article232525871/Prenzlauer-Berg-Hufelandstrasse-wird-zur-Fahrradstrasse-Hufelandstrasse-wird-Fahrradstrasse.html

10. Berlin Mobility Act – Berlin.de. (2022). Berlin Senate. https://www.berlin.de/sen/uvk/en/traffic/transport-policy/berlin-mobility-act/

11. Mitmachen – Pro Kiez Bötzowviertel e.V. Berlin. (2020). ProKiez. https://www.prokiez.de/mitmachen/

12. Start. (2022). Fuss-ev.de. https://www.fuss-ev.de/

13. Berlin Senate. (2022, July 19). Up to 39 degrees: Heat wave reaches Berlin. Berlin.De. https://www.berlin.de/en/news/7634442-5559700-up-to-39-degrees-heat-wave-reaches-berli.en.html

14. Li, X. L. (2019). Urban heat island impacts on building energy consumption: a review of approaches and findings. Elsevier, 1–43. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0360544219303895

15. BMUV. (2020). Water protection policy in Germany. https://www.bmuv.de/en/topics/water-resources-waste/water-management/policy-goals-and-instruments/water-protection-policy-in-germany

16. HafenCity Universität Hamburg (HCU): BlueGreenStreets. (2021). Hcu-Hamburg.De. https://www.hcu-hamburg.de/research/forschungsgruppen/reap/reap-projekte/bluegreenstreets/

17. Jekel & Sieker. (2010). Technical University of Berlin Dept. of Water Quality Control, Rainwater management for urban drainage, groundwater recharge and storage. https://www.hmw.tu-berlin.de/fileadmin/i41_hmw/12_DAAD_Rainwater-Jekel-Chile2010.pdf

18. Senate Department for Urban Development and the Environment and Chamber of Commerce and Industry of Berlin. (2014). Business in Berlin Supports Biodiversity Recommendations for Action – A Guide. https://www.berlin.de/sen/uvk/_assets/natur-gruen/biologische-vielfalt/publikationen/leitfaden_biologischevielfalt_englisch.pdf

19. Biodiversity Policy Lab. (2022). Museum Für Naturkunde. https://www.museumfuernaturkunde.berlin/en/science/research/society-and-nature/biodiversity-policy-lab

20. Parris, K. M., Amati, M., Bekessy, S. A., Dagenais, D., Fryd, O., Hahs, A. K., Hes, D., Imberger, S. J., Livesley, S. J., Marshall, A. J., Rhodes, J. R., Threlfall, C. G., Tingley, R., van der Ree, R., Walsh, C. J., Wilkerson, M. L., & Williams, N. S. (2018). The seven lamps of planning for biodiversity in the city. Cities, 83, 44–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2018.06.007

We battle climate change impacts on urban ecosystems and health across different European climate zones.

Co-funded by the European Union.

We support city makers in implementing sustainable development goals with evidence.